Lead-Up Event #1: “Leaning Out” Screening and Q&A

February 21, 2019

CHICAGO – Expanding on the broader theme of “50 Forward; 50 Back,” the first of four “lead-up” events to the CTBUH 10th World Congress took place at the Chicago Architecture Center, with more than 100 people in attendance. “Leaning Out and Looking Back with Les Robertson,” co-organized by the CTBUH headquarters and Chicago Chapter, presented a 55-minute documentary film about the life and career of Leslie Robertson, CTBUH Chairman from 1985 to 1990, principal of See Robertson Structural Engineers, and lead structural engineer of New York City’s original World Trade Center towers.

“Leaning Out”, directed by Basia and Leonard Myszynski, profiles the life’s work of Robertson, now 91, exploring in-depth his relationship with World Trade Center Twin Towers architect Minoru Yamasaki, and the emotionally taxing task of dealing with the media and ongoing forensics after the towers’ collapse in the terror attacks of September 11, 2001. The film also prominently featured the professional and emotional support provided by SawTeen See, Robertson’s wife and co-founder of See Robertson Structural Engineers.

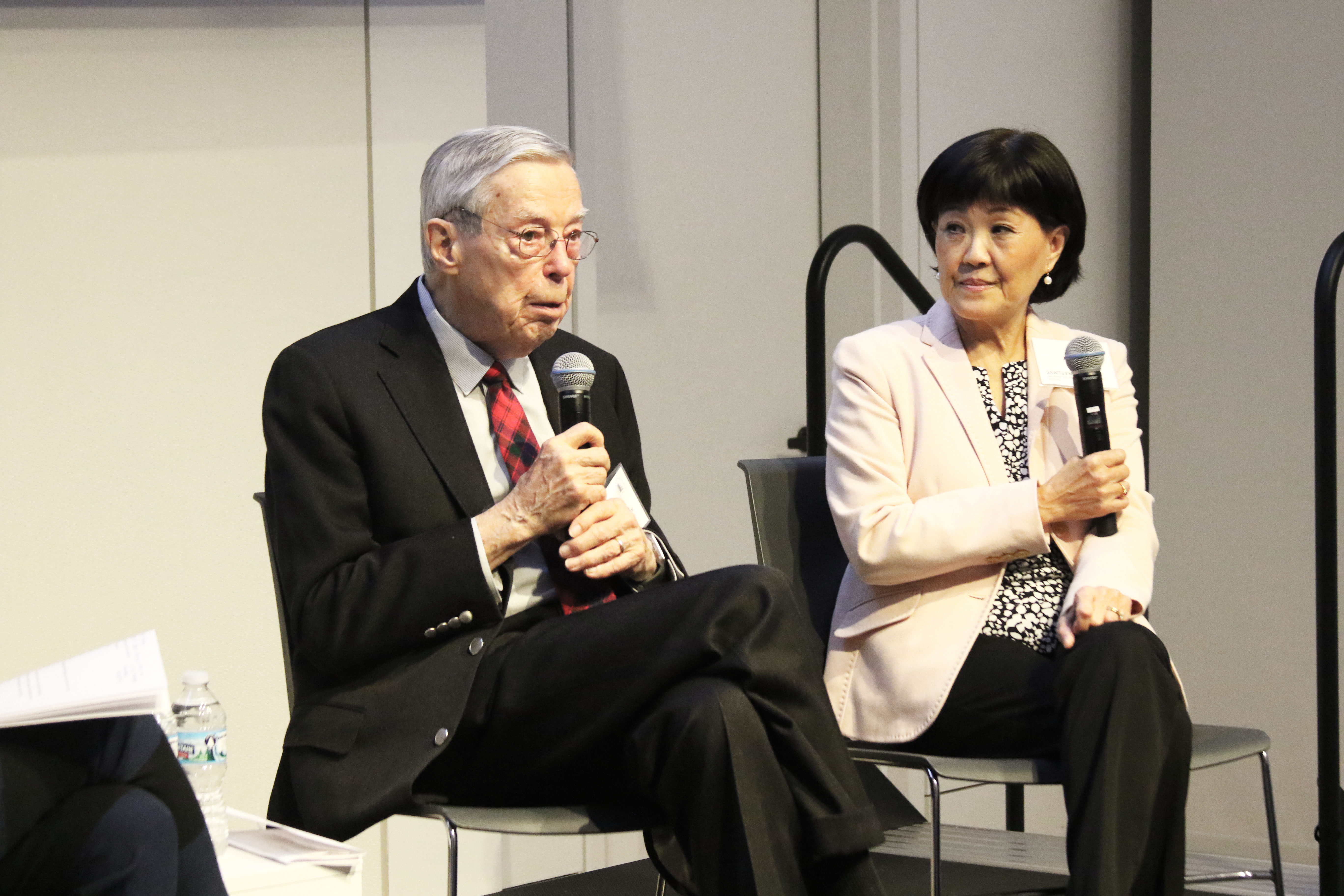

Both Robertson and See were on hand to answer questions, first in a structured Q & A session with CTBUH Chicago Chapter Chair Shelley Finnigan, Global Technical Sales Engineer and Head of Technical Sales & Marketing for ArcelorMittal; and then with the general audience.

CTBUH CEO Antony Wood opened up the session, sharing Robertson’s instrumental role in engineering projects ranging from before the Council’s founding in 1969, to the Bank of China (Hong Kong) in 1990, to the Lotte World Tower, completed in 2017. Prior to the screening, Robertson shared a few thoughts with the audience.

“Let me assure you that I was Chairman in name only,” Robertson said, self-deprecatingly extolling the outsize role of founder Lynn S. Beedle in the Council’s early days. “He was the founder, chief executive, get-things-done guy. He’d call me up every Saturday and go over what I’d done that week at the Council, which was nothing.”

Robertson explained that the “Leaning Out” title had very little to do with tall buildings in concept – instead it was a reference to his three favorite hobbies: rock climbing, skiing and wind-surfing, all of which require the human body to retain a leaning position in order to avoid disaster. By the end of the film, it was clear that the humanistic and physiological aspects of structural engineering and tall buildings are in fact deeply intertwined. No less a figure than Philippe Petit, the high-wire artist who walked between the Twin Towers in 1974, provided testimony to Robertson’s philosophically-infused engineering genius.

After the film, Robertson and See provided further insights on their career and philosophy.

On becoming a structural engineer:

“I sort of snuck in from behind,” Robertson said. “I dropped out of high school, went to college on the G.I. Bill, but I had never studied physics or chemistry, I just worked really hard. I dropped out of college, too, but I came back. I got a job as a mathematician, working in the electrical department of an engineering firm. The head of the group said, ‘we think you should be in structures.’ It came more easily to me than other things, and I’ve been in it ever since.”

“I actually started out in architecture,” See said. “I got a scholarship to study it at Cornell [University]. Back then it was taught with a lot of history and arts – but I was much better at math and science. After the first month, I switched from architecture to engineering. I was still designing buildings but from an engineering point of view. “

On the role of engineers as communicators, and the importance of a well-balanced intellectual life:

“I always say that you are not in the architecture or engineering business,” Robertson said. “You’re in the communication business. I’ve never met a really successful architect or engineer who is not a great communicator. If you’ve had a productive day with an architect or developer, and you go to dinner, you can’t talk about engineering. They won’t know what you’re talking about. It’s terribly dull! You have to talk about the world that surrounds you. The only way to do that is to get out from behind your computer screen and get involved. Learn about music, ballet, painting, sculpture…when I am not at work and conversing with people like I.M. Pei, we talk about the arts.”

On female representation in the field of structural engineering:

“I think it starts very early: parents buy dolls for girls, and trucks and trains for boys. Then in grade school, even teachers think that girls aren’t good at math, and they become pigeonholed,” See said. “When I started at work, there were maybe two other women engineers in the office, and there were no other women to offer mentorship to me. Things have changed a lot since then. The practice was made up of about 5 percent women when I started. Now it may be up to 25 percent,” she said. “But women are still very underrepresented, and I’m not sure how we change that.”

On collaboration between architects and engineers:

“The architect is the one who waves the baton to lead the whole team,” Robertson said. “As an engineer, you have to get your ideas into the architect’s head without them knowing you’re doing it, and be able to extract them back out again, and use them.”

“The client has to understand that every decision comes with some risks and some rewards,” See said. “In the coming together of minds in generating the design, we want the owner to share in and understand how the system works.”

—

Return frequently to the World Congress site for updates on the next “Lead-Up” events.