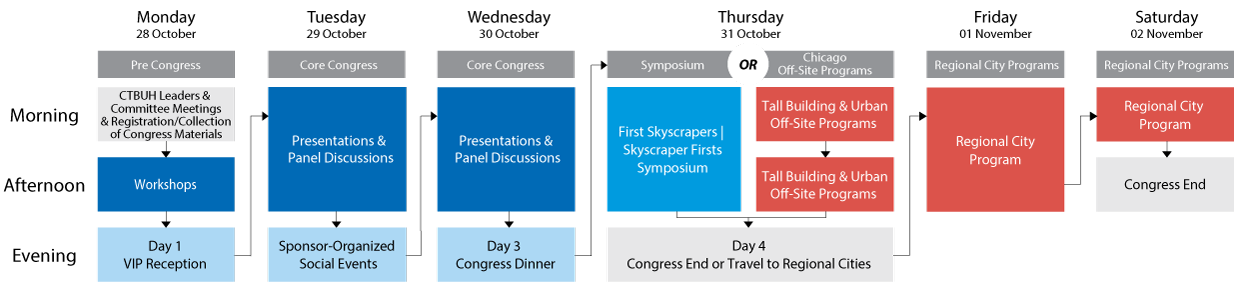

Delegates had the opportunity to engage with the conference for two, three, four, or all six days. Numerous CTBUH Committee and Leader meetings—as well as on-site registration and workshops—occured on Monday 28 October. The core conference of speaker and poster presentations, regional rooms, panel discussions and social networking events occurred on Tuesday 29 & Wednesday 30 October. A stand-alone “First Skyscrapers | Skyscraper Firsts” symposium, as well as Off-Site Programs across numerous tall building and urban venues in Chicago took place on Thursday 31 October. Then, for those wanting to travel on to see the very best of urban development in other cities in North America, there was 1.5 days of regional city programs in Toronto and New York City.

50 Forward | 50 Back: The Recent History and Essential Future of Sustainable Cities

On the 50th anniversary of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat’s founding, the CTBUH 10th World Congress returned to the Council’s home: Chicago. Focusing on the theme 50 Forward | 50 Back, the Congress explored the most significant advancements in tall buildings and cities from the last 50 years, whilst inquiring into the future of our cities 50 years from now. This event thus represented a critical reflection on both the skyscraper typology and urban development as a whole, by marking their trajectory to date, and considering the evolutions that must take place to accommodate a dynamic and uncertain global future.

Fifty years ago, in 1969, plans were put forth to build the Sears Tower in Chicago, a 442-meter skyscraper that would take the title of “World’s Tallest Building” when it completed five years later.1 That same year, the New York City Planning Commission released the Plan for New York City,2 a six-volume tome that sought to refocus attention on neighborhood-level improvements, as a way to soften and humanize the ill effects of numerous urban-renewal schemes that had decimated cities for the previous two decades. The tension between human-centric and technologically-advanced design progress was brought into sharp focus at this time—but, arguably, has never truly been resolved.

Since that time, cities have grown exponentially, all incorporating—in some way—the lessons and technologies of those that came before them. Whereas only 37% (1.3 billion) of the global human population lived in urban areas in 1969, today that figure has increased to 55% (4.2 billion), with further urban growth projected at 68% (6.7 billion) by 2050.3 Close to 90% of this growth will take place in Asia and Africa. But not all urban areas are destined for unabated growth. Those vulnerable to natural disasters or severe economic instability may see major population losses, as residents seek out locations with fewer crises and improved education, employment opportunities, health services, and housing.

On a building scale, the manifestation of the contemporary skyscraper is a collective accomplishment—one that has experienced several wholesale evolutions over time. Whereas back in 1969, at the formation of the CTBUH, the tall building was predominantly a technical challenge, now it is, arguably, more of a social challenge—how does it fit in with, and enhance, society? With the technological barriers towards height now largely addressed, an emphasis is being placed on making more humane, smarter, greener, more efficient skyscrapers that are better integrated with their cities, and better stewards of the urban environment. But much still needs to be done.

We thus stand at a critical juncture in time, amidst major change in the typological status of tall buildings, the cities they call home, and the people that inhabit them. The 10th World Congress, Chicago,4 directly addressed critical issues in the future progression of our cities, drawing the most important lessons from the past. All relevant issues—including urban planning and infrastructure; smart technology/automation; resilience and climate change; passive environmental strategies; tall timber structural systems; modular construction; inter-/intra-building transportation; the future of the workplace; building modeling; and many others—were explored.

The Congress also hosted a number of Regional Rooms, encapsulating a geographic audit of the best developments in each region around the world. In addition, there were major Program Tracks on themes relating to the overall conference theme, encompassing the core-conference presentations and panel discussions, exploring topics in depth. And, being the Council’s 50th year, there were several special events leading up to the Congress and at the event itself, marking this important occasion. These included the formal Congress/50th Anniversary Dinner and the naming of the 50 Most Influential Tall Buildings of the Last 50 Years.

Footnotes:

1. The Skyscraper Center, CTBUH

2. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Plan for New York City. 1969. A proposal. New York City planning commission.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed September 18, 2018. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c42cb93f-8db0-ca65-e040-e00a18064e5c

3. 2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects, United Nations

4. The Council holds at least one conference per year and a world congress every five years in an active tall building city around the world. Larger in scale than the annual conferences, world congresses are substantiated by paper-based proceedings and encapsulate a geographic audit of the best developments happening in each region around the world.